“Disaster makes for fantastic distraction.”

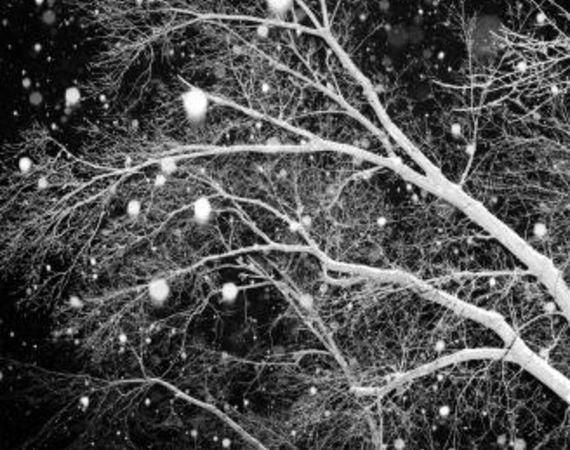

In the early winter of 2010 we had a storm that produced unusually heavy snow. At the time I was experiencing a period of depression. One of my symptoms was insomnia of a sort that would have me waking up several times a night. During the night of the storm I’d rise every two hours or so, look out the window, and marvel at how large and solid the snowflakes were.

The falling of snow was as relentless as was my wakefulness; no matter the hour, it was always going full bore, a great mass of snowflakes obscuring the view. Through the torrent of white I could see the snow accumulating on the shrubs and trees. Some of the branches were bowed nearly 180 degrees, their tips having gone from pointing skyward to forming a hairpin curve down to the ground.

In the early morning the storm finally abated. But then the temperature dropped, freezing the wet snow to its hosts. A thick epidermis of snow covered the world and muffled all its sounds save for one: the sound of shattering wood. Every few minutes a noise like a shot would split the air and echo down the block. Moments later a branch would give way at the joint and come crashing down. Our house is surrounded by old growth trees, some of them approaching 70 feet tall. We stopped going outside because it was so obviously dangerous.

I sat inside on the couch, in a house without power. All I could do was sit, listen and wait. Waiting for our branches to fall, which many of them did over the course of the day, became almost meditative, and the inevitability of each new piece of damage almost gratifying. Whereas in the previous weeks I’d been locked in a kind of inner dread and vigilance, those feelings were now directed completely outward. My deafening mental tape loop of unhappy machinations had been silenced, however temporarily. I couldn’t afford to listen to it during those hours. There was too much going on outside. I needed to pay attention.

I did not want those branches to stop falling.